Black Swan Approaching? US Treasury Bonds Trigger Chain Crisis! Institutions and Central Banks Already Taking Action—How Should You Respond?

Will there really be a crisis in US Treasury bonds? Just a few months ago, at Warren Buffett's last shareholder meeting, he was asked this very question. Buffett’s answer was quite thought-provoking. He said that the government is not subject to any constraints, the fiscal deficit is making US debt unsustainable, and we are already very close to a crisis.

In fact, it's not just Buffett; recently, various Wall Street moguls have stepped forward to warn about the US debt issue. JP Morgan CEO Jamie Dimon admitted in his 2025 letter to shareholders that such huge fiscal deficits are unsustainable. We don't know when it will erupt and bite, but a US debt crisis is bound to come. Goldman Sachs CEO Solomon also said: The US debt issue will eventually face a reckoning. Bridgewater founder Ray Dalio has already begun to reduce his exposure to long-term US debt and increase holdings in gold and non-US assets.

So what exactly is it that is making these Wall Street elites start worrying about US Treasuries at this point in time? And why is 2026 said to be an important turning point for US debt? For ordinary investors like us, how will this risk—long thought of as a black swan in the US stock market—affect us? And how should we respond? In today’s video, US Investment Pro will have a good talk with everyone about the increasingly severe US debt issue.

What is the US debt crisis?

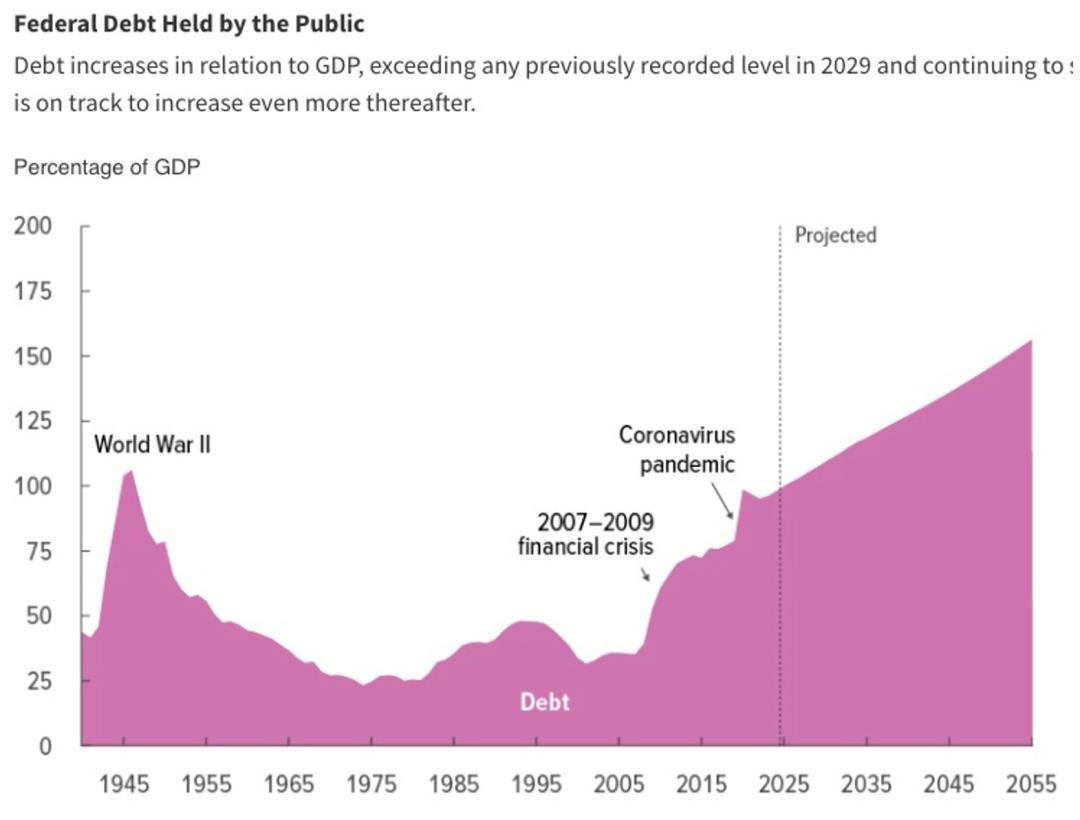

To start with, US Investment Pro wants to show everyone a chart. This is the proportion of US national debt to GDP over the past 100 years. You can see that the proportion of US debt to GDP is now as high as 120%. The last time the US debt was at today’s level was back in World War II. According to the US Congressional Budget Office (CBO), this scale of debt will continue to expand over the next 30 years. Judging from the chart, it won’t take two years to surpass the WWII peak and become the highest in history.

But keep in mind, the past 20 years have been peaceful times. If you didn’t know, you might think a third world war is coming. In reality, the surge in US debt over the past decade or so is mainly due to two unprecedented economic crises: the 2008 financial crisis and the 2020 pandemic. The chart also shows that these two major crises triggered a steep rise in US debt.

On the surface, the expansion of US debt is the government pumping money into the collapsing US economy. But in reality, it’s far more complicated. If it were that simple, why did so many historical crises never see this kind of debt expansion? And why does US debt keep growing even after both crises have passed? There are even greater dangers hidden behind this, which we'll discuss in detail later.

Just based on current trends, it's clear that the US government is now on an out-of-control spending spree with no sign of slowing debt growth. For those unfamiliar with the US debt mechanism, let me explain briefly: the US debt problem is essentially a problem of fiscal deficit—because the government spends more than it earns each year, it needs to keep borrowing to cover spending. In the analysis below, sometimes these two terms will be used interchangeably. Now you can see that this endless expansion of debt is almost certainly unsustainable. Once there’s a problem with US debt, it’s going to be a massive problem. At this point, it’s only a matter of when, not if. That’s the fundamental reason why so many on Wall Street are worried.

Here’s the question: US debt’s unchecked expansion isn’t new. For more than a decade, US debt has been growing without control. So why has this issue suddenly become urgent right now? How serious is it? To answer that, we need to start with events in 2025 that have fundamentally changed the landscape of US debt.

Signals of a US debt crisis

The first major structural change was the complete shelving of DOGE, led by Musk. Just two months ago, the US Office of Personnel Management (OPM) confirmed that DOGE, as a centralized entity, no longer exists—the whole department quietly disappeared from public view. Looking at the result, although the federal civil workforce was reduced, expenditures actually rose: in the first 11 months of 2025, federal spending was about $7.6 trillion, $250 billion more than the prior year. It’s clear that the much-touted DOGE budget cuts had little real effect.

I know that when it comes to DOGE, many people may scoff at it, thinking it's just a toy created by a few willful old boys, but that's not the case. The shelving of DOGE has become an important signal event for US debt risk.

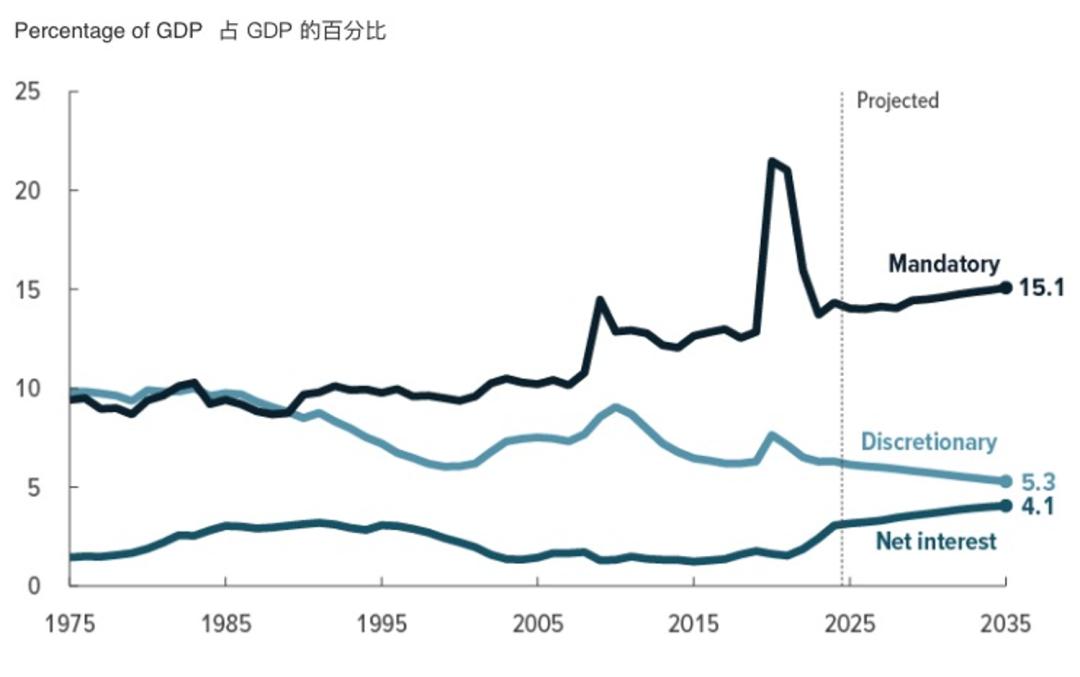

To be fair, cutting government spending is objectively very difficult. The chart below shows that the biggest chunks of government spending are the hardest to cut. These include entitlement commitments, defense, interest payments, and various politically mandated programs. There’s almost no room for maneuver. The remaining discretionary spending is also naturally constrained by the US political system, which we’ll discuss in more detail later.

Given these objective conditions, relying on traditional politicians to solve the problem is almost hopeless. Many people pinned their hopes on someone like Musk—outside the political system, with a strong sense of purpose and willing to do whatever it takes to solve spending issues—hoping he would make bold moves to ease the US debt crisis at its root. After taking office, Musk really did go all in, offending almost every politician in both parties and even many Tesla users. Unfortunately, even the person considered most likely to solve the problem in the world couldn't push it forward. Looking ahead, the chances of truly solving the US debt problem are now extremely slim. This is a strong signal for US debt risk, and we’ll discuss the specific impact later.

The second major structural change occurred almost simultaneously with the shelving of DOGE: the passing of Trump’s "Great America Act." This is also a signal event.

Trump’s "Great America Act" can be considered his most important economic policy during his term. The key policy was massive tax cuts for individuals and businesses, meaning government revenue fell even further. On the spending side, people were surprised to see that Trump—a champion of small government, spending cuts, and a fierce opponent of Biden's handouts—still kept most government spending intact. In other words, the Act not only failed to restrain the fiscal deficit, but pushed the borrowing and spending trajectory to new extremes.

Some might say: don't just look at the "Great America Act"—didn't Trump say he’d raise tariffs to make money? True, this was seen as key to easing the deficit, but in practice, tariffs were more of a bargaining chip, and the actual revenue was hardly enough to make up the massive gap. According to the Congressional Budget Office, tariffs could bring in $2.3 trillion, but the "Great America Act" would add $3.4 trillion to the deficit, leaving a gap of about $1 trillion. The deficit is destined to keep growing.

Like Musk with DOGE, Trump was seen by many as a president capable of radical change. After his election, people had high hopes he’d solve the debt problem.

On one hand, many blamed the debt crisis on Democrat Biden’s reckless spending, and hoped a change in party would fix it. Trump is a classic non-traditional politician, and his Treasury Secretary, Besant, came from the financial sector and was also unconventional. People hoped these two would ignore political constraints and rein in spending.

On the other hand, the US economy has been very strong in the past two years, providing the best soil for fiscal tightening. There’s a saying: “You should repair the roof when the sun is shining.” Logically, with a strong economy, it’s time to raise taxes or cut spending. However, Trump couldn’t escape the political system's grip, and in the best moment to cut spending, he still went wild on handouts. What does this mean? It means that even the much-anticipated Trump could not break convention to reverse the US debt predicament. Clearly, this is another strong signal for US debt risk.

The risk is intensifying

In 2025, besides these two signal events, two worsening trends have made the US debt situation even more serious. First, after Trump took office, political polarization in the US became extreme. This phenomenon needs little explanation—you can all see it. So how does this affect US debt?

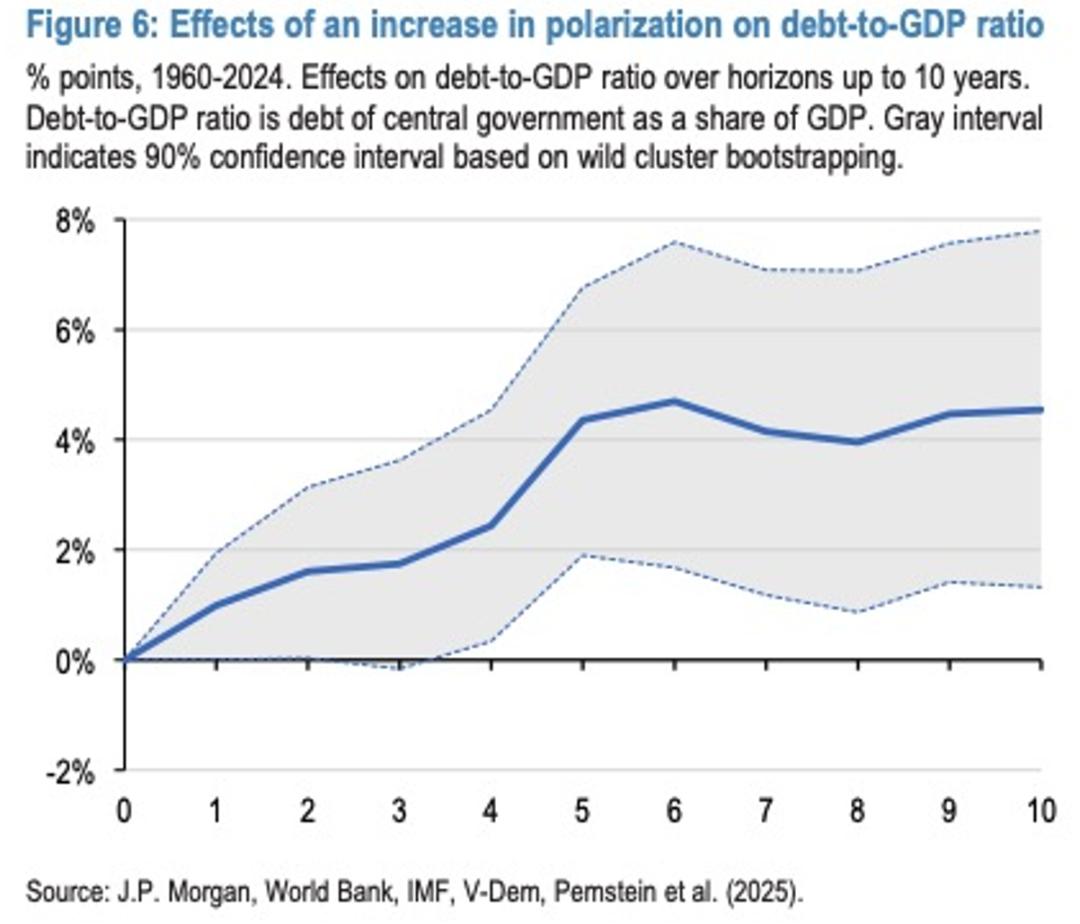

Because any major reform inevitably requires major sacrifice. It must be a process of compromise, and in the US political system, compromise is never a one-party affair—it requires both parties to give up some interests and reach a result through negotiation. Political polarization obviously makes such reform extremely difficult.

History has proven this countless times. Research shows that in politically polarized developed economies, debt ratios almost always keep rising. That’s because debt expansion is the path of least resistance—neither party wants to make changes.

Second, the trend of de-dollarization is intensifying. This dates back to the Russia-Ukraine war in 2022, when the US froze Russia’s dollar assets as a sanction. This marked the beginning of the weaponization of the US dollar. Other dollar-holding countries realized that dollar assets are actually not safe. This is no small matter, because for most countries, US Treasuries are the main foreign exchange reserve. The weaponization of the dollar means that if relations with the US sour, my treasury could be frozen by the Americans at any time.

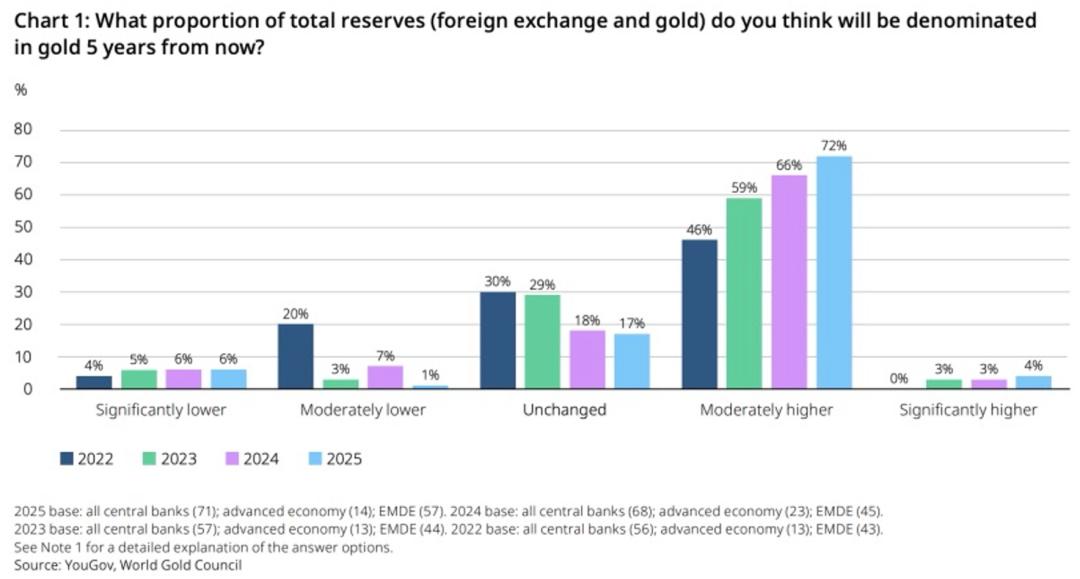

Over the past year since Trump took office, US foreign policy has made more and more countries want to reduce dollar reserves. The World Gold Council’s 2025 global central bank survey shows that 76% of surveyed central banks say the proportion of gold in their reserves will rise moderately in the next five years, replacing US Treasuries. In 2022, this ratio was just 46%, and it has shown a steady increase every year. This is also a key growth driver for gold—on US Investment Pro, I just published a 2026 gold investment outlook, analyzing gold’s opportunities and risks in detail and sharing my short- and long-term price views. Interested readers are welcome to check it out.

So, as you can see, we’ve seen two major structural changes in US debt in 2025, as well as two worsening risk trends. This basically explains why, at this moment, concerns about US debt are rising sharply. So, the next question is: how will the US debt crisis develop in the foreseeable future? The answer will directly decide how investors should act.

What will happen in the future?

Is US debt really doomed? Maybe my view is pessimistic, but in my opinion, a US debt crisis is inevitable, and it may not be far away.

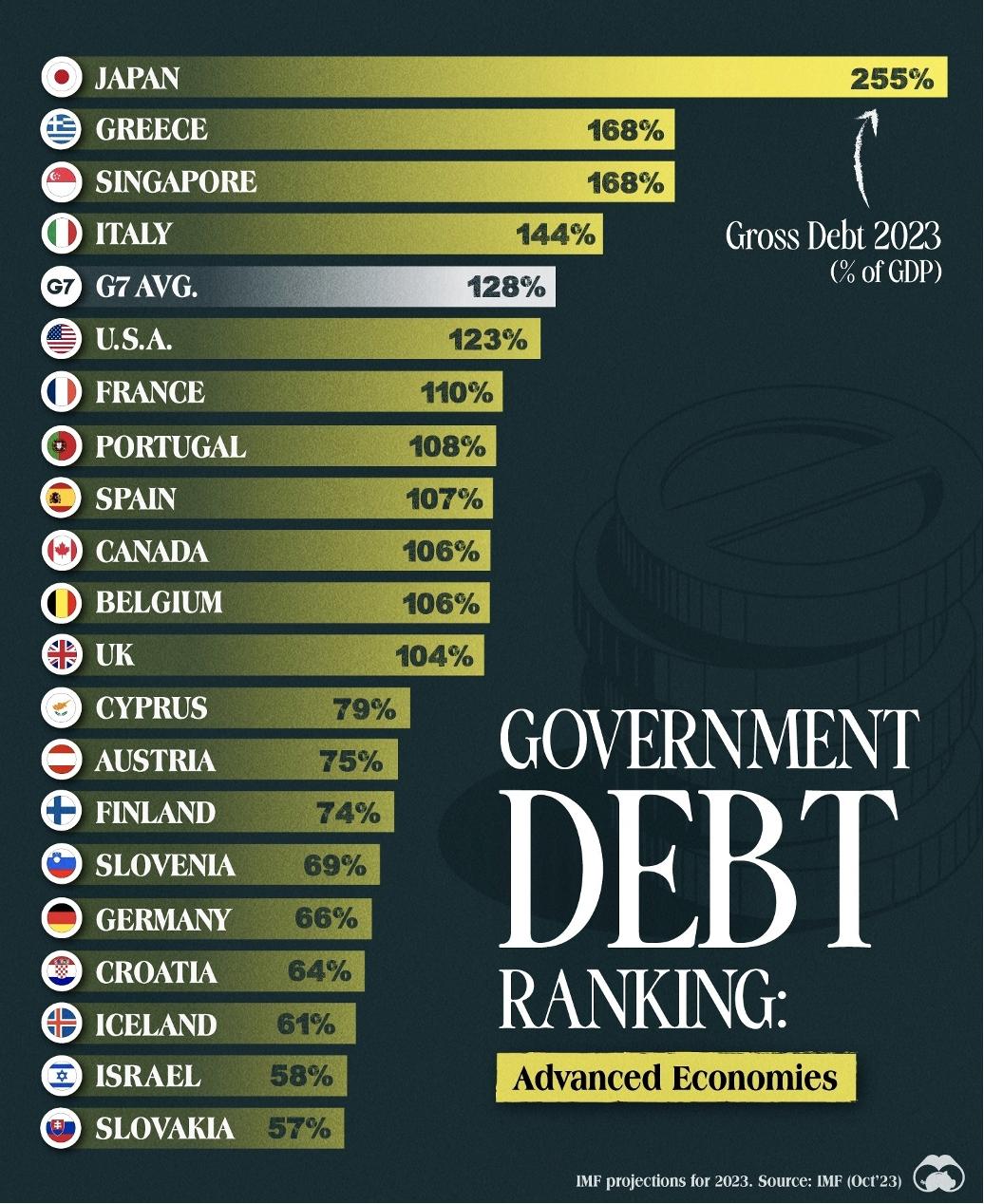

Regarding the US debt crisis, investors must first break a misconception. Many people think the problem is the continuous expansion of US debt. Actually, that's not the problem. Thanks to the dollar's hegemony, like it or not, the US does have room for healthy, sustained debt expansion. Honestly, looking at the current debt-to-GDP ratio of 123%, it seems exaggerated, but globally, it’s not—it’s far below Japan’s 255%, and is about average among the G7 countries.

The real issue with US debt today isn’t its scale, but the complete disappearance of its correction mechanism. To understand this, we need to introduce the concept of "skin in the game," from Nassim Taleb’s book "Skin in the Game." It means: whoever makes the decision bears all the consequences. Only then does the system have a self-correcting mechanism and remain stable. On the contrary, if you enjoy the benefits of your decisions but others bear the risks, then risk will inevitably accumulate until the system collapses and becomes fragile.

"Skin in the game" can be seen as the first principle in policy making. In the 2008 financial crisis, the problems were caused by big bankers. They made huge profits during the subprime bubble, but after the crisis, most walked away unscathed, and big institutions survived just fine. The real losses were borne by countless American taxpayers.

Similarly, during the 2020 pandemic, the Biden administration’s money printing did rescue the economy and won votes and praise, but the resulting deficit and debt risk will not be borne by Biden’s administration but left to successors and the American people. All these are classic "anti-skin-in-the-game" behaviors, making the system inherently fragile.

Looking back, we find that similar "anti-skin-in-the-game" actions always end badly. In the 1990s, Japan propped up big companies after its bubble burst. In 2010, China’s 4-trillion stimulus artificially boosted fragile real estate and export sectors. The results were obvious: these are classic fragile systems.

Note, we’re not saying such actions are always wrong, just that they are inherently fragile. You can do it, and in the short term it may be fine, but if it’s not checked, risk will inevitably accumulate to the point of collapse.

The US situation is even more subtle. Not only have policies created a fragile system, but the political system further encourages "anti-skin-in-the-game" behavior. In a democracy, politicians’ decisions follow short-term public opinion, making populist politicians the best solution. For ordinary people, anyone would want low taxes plus high benefits like healthcare and pension. So politicians keep increasing spending to win votes and the debt snowballs. This creates a vicious cycle—no one wants to change the status quo.

So, under the first principle of "skin in the game" and the US political system, a US debt crisis is almost unavoidable. But that’s not the most worrying part—the worst is the total failure of the correction mechanism.

In the past, politicians could enjoy spending but still feared risk—after all, who knew if a spending spree would bring immediate consequences? But the 2008 and 2020 crises forced politicians to spend big. Afterward, they nervously waited for a backlash, but nothing happened. Having tasted the "forbidden fruit," politicians became reckless. Now, no one wants to correct the course, because there are no short-term rewards for doing so. With the last bit of fear gone, the fragile system is even closer to collapse.

It’s not that no one sees this. Treasury Secretary Besant and DOGE’s Musk both expressed similar concerns when first elected. I believe they truly wanted to solve the US debt problem. Yet reality dealt a heavy blow to anyone with ideals. In the end, even those with the best chance of fixing the problem—or the last to possibly reverse the situation—also failed.

Going forward, the current US debt is like a speeding old car that’s lost its last brake. An already fragile system is now racing headlong into unknown risks.

What will be the consequences?

If you carefully consider all US debt risks, you’ll find that in 2026, the biggest change is not the fragile old car or its speed, but the loss of its last brake. In other words, from this moment, expectations about US debt risk have fundamentally changed. It’s no longer a dangerous but controllable problem—it’s now dangerous and uncontrollable. So what will be the end result?

First, this long-term change in risk profile will almost certainly prompt institutions with long-term allocations to act, most importantly central banks and pension funds. These institutions won’t sell quickly, but will gradually and persistently reduce their US debt holdings. This means US Treasuries—especially long bonds—will face long-term downward pressure, while yields (long-term interest rates) will face long-term upward pressure.

Rising long-term rates affect the entire financial market: they set the base for mortgage rates, anchor for credit bonds, and are a key determinant of the dollar exchange rate. Most critically, they underlie risk asset valuations. If long-term rates rise, all risk assets will face valuation pressure.

Beyond finance, higher long-term yields raise government borrowing costs, making the US fiscal situation—already under deficit pressure—even worse. Continuing deficits further reduce US debt’s appeal, pushing rates up again. In the worst case, this could create a vicious cycle.

Second, an oversized US debt brings greater inflation risk. Under heavy debt, governments are actually incentivized to promote inflation, because high inflation can dilute debt. On the other hand, fiscal deficits themselves bring inflation. Both will affect market expectations for inflation and cause asset price fluctuations.

Third, unchecked expansion of US debt squeezes policy room. In the past two major economic crises, the US borrowed its way out of recession. But now, the ammo is running out. If another crisis hits, with debt and interest burdens already high, large-scale stimulus will be hard, and even if it’s possible, it may have little effect. After all, “stimulus” works less and less over time. The next economic crisis could be magnified and last longer.

How will this ultimately end? I think in the end, only a major crisis can force a reset. In fact, something similar has happened in US history. In the 1970s, both the US and Europe pursued big government, providing benefits to people but timid about raising taxes, causing deficits to soar and keeping the West under threat of high inflation. This period was later called the "Great Stagflation Era." After a decade of pain, the West finally saw strong leaders like Reagan and Thatcher, who changed the course.

In my view, the appearance of Reagan and Thatcher was not accidental, but historically inevitable. Only when voters truly feel the impact of government debt and deficits can real change happen. For us today, I believe it will be the same. Only extreme pain brings extreme reform—maybe only after voters experience this pain will a reform-driven leader emerge.

What should investors do?

By now, some readers may be getting nervous. Since US debt risk is inevitable, should we sell all our stocks to avoid risk? Personally, I don’t think so! My analysis here is not alarmist, nor am I saying a crisis will erupt tomorrow. In fact, at present, there is no risk of US debt default. What has truly changed is not the probability of default, but the risk structure of US debt, which will have long-term effects on the market—all those effects we analyzed above will play out over the long run.

Even in the worst case, if US debt risk does materialize, I still don’t think we should liquidate all stocks to avoid risk. Responding to long-term risk structure changes is what central banks and big institutions must do, but for ordinary investors, the best way is still to keep investing. No one knows when risk will hit, and looking over the past century, the US has faced many crises—each seeming worse than the last—but the stock market always recovered quickly and went on to new highs.

So for ordinary investors, the first thing is to keep investing. If you really want to hedge against this risk, I personally think the best way is to invest in anti-fragile opportunities that can survive across cycles. Let me mention a somewhat counterintuitive target: AI stocks. I’m not saying these won’t fall during a crisis—they certainly will. But high-quality AI companies can survive across cycles, because AI technology will not stop progressing, regardless of economic or financial crises. This is a good example of an anti-fragile investment opportunity.

In addition, gold and bitcoin are also good choices to hedge against a US debt crisis. Gold is a substitute for US Treasuries—if there’s a problem with US debt, people will first think of gold. So if a market crisis emerges because of US debt, gold may rise, providing a hedge and diversification. Bitcoin is also regarded as an important asset against fiat currency, sharing properties with gold and can be used for asset allocation. But note—I’m emphasizing asset allocation here, not that it will definitely rise tomorrow.

Conclusion

Alright, that’s all the analysis on US debt risks. What’s your view on US debt risk? Feel free to leave your opinion in the comments.

Alright, that’s all the analysis on US debt risks. What’s your view on US debt risk? Feel free to leave your opinion in the comments.

Disclaimer: The content of this article solely reflects the author's opinion and does not represent the platform in any capacity. This article is not intended to serve as a reference for making investment decisions.

You may also like

Ethereum : Buterin reveals major upcoming reforms

Samsung set to hand out record bonuses as AI boom translates into profits

Bitcoin Gains Traction As ETF Demand Surges

Bank of England raises concerns as hedge fund positions in gilts reach £100 billion